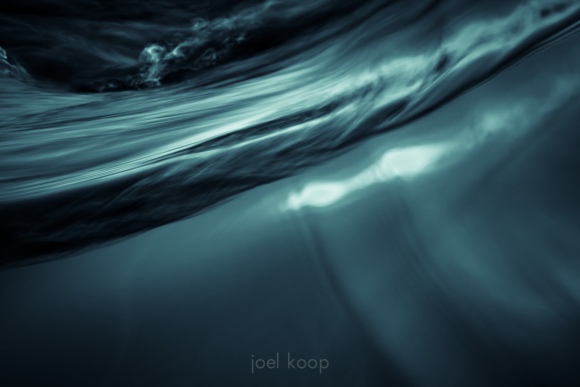

Ice on the Sunwapta River

Canon 5d with Sigma 150 macro

150mm, f5.6, 1/160 of a second

Lately I’ve been reading and thinking about the relationship between photography and art. It seems a lot of photographers define what they do as art and what many other photographers are doing as “not art”. Occasionally they try to soften it by saying that this is not a value judgement, but it’s impossible to remove that implication. Some say you have to pre-visualize the shot for it to be art, some claim there has to be a meaning, some claim that it has to involve creativity or originality. I say whether your work is art (or has artistic value) will not be decided by you. You only have a small amount of influence over the perception of your work. The best you can do is do what you love and let the chips fall where they may (unless you have an unusually large influence on a large number of people).

Guy Tal, a great inspiration and talented photographer, has been writing about photographers who go to commonly photographed natural icons and take photos similar to those taken thousands of times before. While I agree with most of his points (and I don’t find these photos very interesting), I think their value is not for me to decide. I tend to value the unusual (combined with beauty and/or story), as I think a lot of people do. The problem with valuing the unusual is that, for example, the rock arches in Utah are very unusual — until you’re looking at a photo that looks the same as 500 others you’ve seen. So even though 20,000 photos of this exact subject may exist, the first one you see will strike you as an incredible work of art. And as a photographer the same applies. If you haven’t seen a single photo of the arches before, you’re going to take one and think it’s incredible.

Unintended cliches are a common hazard for any artist. This is why it’s important, if you want to be considered an artist, to be aware of other work going on in your field. The problem of dishonesty is a much bigger issue. If a photographer is pretending their work is unique to an uneducated audience, then this is (possibly) a brilliant business strategy but has little to do with art. And of course trying to exactly copy another photographer’s picture and claim it as your own is completely unethical.

Artists over the centuries have stolen ideas, compositions, color schemes, and all sorts of things. This is common practice and good practice — as long as you have a unique perspective on it, ideally one that is recognizably yours. I’m constantly thinking about what defines my perspective (you do need an artist statement after all). While thinking about your perspective or statement is important, I’m not sure the conclusions are an essential part. In the end, your perspective will either show up in your work or it won’t, whether or not you’re aware of it. I think your perspective shows more when you feel free to be yourself than when you chase the idea of being someone else.

What I do is take photos that come from my own unique curiosity and interest in our world. I don’t plan this out (which may rule me out of the art world for some people). I don’t always make challenging political or societal statements with my photos. I take the photos that interest me most and that I enjoy taking. Other people can decide if it’s art — I’m too busy doing what I love (and editing that pesky artist statement).